Can the rand rescue Zimbabwe’s economy?

Tendai Biti sits in his office in a leafy Harare suburb, contemplating another collapse of the Zimbabwean economy.

Thanks to a chronic shortage of US dollars, the country is running out of cash. There are long queues outside every bank, with some customers forced to wait overnight for a chance to withdraw a maximum of US$50 from their account. Businesses are struggling to import stock, renters can’t pay their landlords, and even government is having trouble processing salaries on time.

“The economy is in a hole – a deep hole,” says the man generally credited with rescuing Zimbabwe from its last collapse.

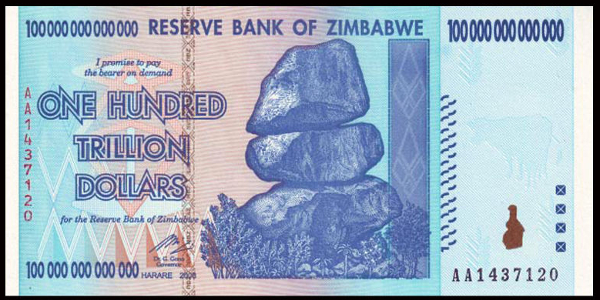

In the 2000s, as Robert Mugabe’s regime started printing money to finance their re-election bid, the Zimbabwean dollar was subject to Weimar Republic-esque levels of hyperinflation. At one point, the Reserve Bank printed a 100-trillion Zimbabwean dollar note. Supermarket shelves were empty, unemployment soared, and supplies of food, petrol and medical supplies ran dry.

When the Government of National Unity came to power in 2009 – following a bitter and violently contested election – Biti, a constitutional lawyer and veteran opposition politician, was appointed finance minister. Under his watch, Zimbabwe abandoned the Zimbabwean dollar, replacing it with a ‘basket of currencies’, a selection of other countries’ currencies that would be considered legal tender in Zimbabwe. These include the US dollar, the euro, the Botswana pula, the South African rand, and the Chinese yuan, among others.

But it was the US dollar that reigned supreme in Zimbabwe’s shops and on its streets, becoming Zimbabwe’s de facto principal currency, as Biti knew it would. And while there is no doubt that this stabilised the economy, and gave Zimbabwe several years of much-needed economic growth, it was never meant to be a permanent fix. According to Biti, it was a temporary measure, designed to keep the country going until it could introduce the South African rand, or some version of it.

“The SADC [Southern African Development Community] monetary union was supposed to be a reality in 2010. My exit strategy then was to adopt the regional currency, which to all intents and purposes would be a rand by another name. But in 2010, I realised that the regional currency was not coming. So I tried to make Zimbabwe join the rand monetary union, but I met resistance from Mr Mugabe and the bankers association,” said Biti.

SADC has been talking about implementing a regional currency for years. But that 2010 deadline came and passed, and Zimbabwe was stuck with the US dollar – and there’s no sign that the regional currency will become a reality any time soon. But given the volume of trade between Zimbabwe and South Africa, Biti says it would have been wiser to promote the rand as Zimbabwe’s de facto principle currency. “I still believe that Zimbabwe ought to join the rand monetary union,” said Biti.

Had Biti succeeded, Zimbabwe might not be facing the cash crunch it is now.

Morgan Tsvangirai, leader of the Movement for Democratic Change-T and prime minister in that Government of National Unity, says it is not too late to adopt the rand. He dismisses the current government’s plan to introduce dollar-backed ‘bond notes’ as doomed to fail – a position shared by most economists – and said that turning to South Africa is now Zimbabwe’s only option.

“Because we don’t have economic ties with the United States, because our trade with the United States is negligible, it means that our dollarisation policy makes our economic policies here more expensive. The only thing that is there, that is feasible, is to have the rand as a legal tender. Ninety-five percent of our trade is with the rand. Why avoid the inevitable, which is that Mugabe has to swallow our so-called sovereignty and say yes, I have to negotiate with South Africa,” said Tsvangirai in an interview.

So what would this look like in practice? Economist Russell Lamberti is the co-author of When Money Destroys Nations, a forensic account of how and why the Zimbabwean dollar collapsed. He explains: “Zimbabwe has numerous options for currency reform. One would be to set up a currency board, which is a legislative requirement to back a ‘new Zim dollar’ at a fixed parity to the US dollar or to the rand, or to a weighted FX basket, with no monetary policy discretion by the RBZ. Another option is to fully adopt the rand in negotiation with South Africa.

“In this case, Zimbabwe submits its entire monetary and financial system under the regulatory jurisdiction of the SARB and Zim banks become subject to the SA repo system. Alternatively, Zimbabwe could have a laissez-faire monetary system in which there are no legal tender laws and no state currency.”

For Lamberti, there are no major economic hurdles preventing a rescue of Zimbabwe’s economy, and adopting the rand would be one viable option to achieve this. A larger challenge, however, is political. “In principle, monetary reform is not that hard in Zimbabwe, whichever option it were to choose. The real problem is political. As long as the state is run as a fiefdom and industry is systematically destroyed and productive people looted from, there is little hope. Mugabe knows that meaningful currency reform diminishes the ability of the state to loot the country. That is the big hurdle.”

Elsewhere in the region, the rand has been adopted with some success. Although Lesotho, Namibia and Swaziland all maintain their own currencies, these are all pegged to the rand, and the rand is widely accepted for trading purposes. Botswana pegs its pula to a basket of currencies, with the rand given the greatest weighting.

Economist Phillip Haslam, Lamberti’s co-author, argues that the rand could bring some immediate advantages to Zimbabwe, including the virtual elimination of currency fluctuations for cross-border trade. But he has an even more radical proposal to rescue the country from its currency woes: the bitcoin. Invented in 2008, bitcoin is a digital crypto-currency that is generated by harnessing the processing power of computers. It is not backed by any government or central bank, which might make it easier for Zimbabwe to adopt without sacrificing too much autonomy.

“We are very excited about bitcoin as a stable currency alternative. The thing about bitcoin is once you import it into the country, you don’t have the problem of the currency eroding and perishing like you have with notes. It’s a system that allows for privatised banking. Effectively, the bitcoin system is both a currency and international payments platform.

“If Zimbabwe establishes a privatised bitcoin national currency, if the market naturally went to a bitcoin type currency, as other currencies around the world indicate weakness with money printing happening, you’d have a whole lot of currency flowing into Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe would transform from a basket case to a global banking centre in a stable crypto currency. And that would be fairly quick.”

It’s an interesting idea, although unlikely that any of Zimbabwe’s decision-makers will adopt such a radical proposal. But it illustrates the greater truth: that, with political will and far-sighted policymakers, there are paths out of Zimbabwe’s current economic malaise. Adopting the rand is one.

Simon Allison is an ISS consultant. This article was originally published by the Institute for Security Studies on ‘ISS Today‘.