Zimbabwe prepares to print money again: What to expect

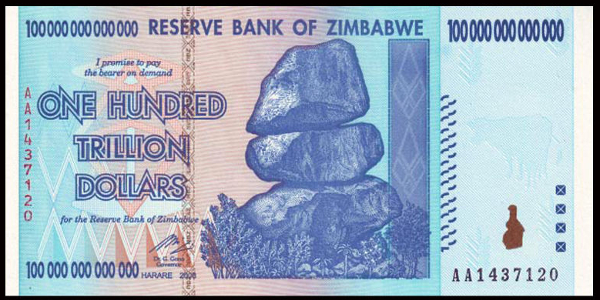

Fears loom that the printing of the Zimbabwean bond note will result in a repeat of the hyperinflation seen in 2008, which saw the infamous Z$100 trillion banknote come into play.

Last week the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe’s governor, John Mangudya, unnerved many when he announced the country would start printing money again in the form of ‘bond notes’. After all, no one has forgotten the last time the central bank printed money in 2008 – where Zimbabweans experienced a monthly inflation rate of 3,500,000%, saw food prices double daily, and were transacting in trillion dollar banknotes.

The new Zimbabwean bond notes will be printed in denominations of $2, $5, $10, $20 and be valued one-on-one with the US dollar in an attempt to solve the country’s cash shortage. Up to US$200m-worth of bond notes will be issued and they are expected to be in circulation within the next two months.

According to Mangudya, they are intended to encourage exports and will be used to pay a 5% incentive to exporters, and then circulate into the market. But many believe it will not retain its value.

A cash crisis

Zimbabwe is currently under severe constraints imposed by a shortage of cash in the economy.

The country was forced to ditch its Zimbabwean dollar in 2009 after experiencing one of the worst cases of hyperinflation in world history. It adopted a multicurrency system (starting with the US dollar) with the aim of improving cash supply, and the central bank has since authorised nine currencies as legal tender. These include the South African rand, euro, Botswanan pula, British pound sterling, Chinese yuan, Indian rupee, Japanese yen and Australian dollar.

The US dollar has, by far, remained the preferred and most widely-used currency in the market, but its supply has been dwindling. With very little local manufacturing activity, the country has an over-reliance on imports – which is mostly paid for in US dollars.

Between January and November last year Zimbabwe’s imports stood at $5,8bn while its exports were only $2.8bn, according to Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. The $3bn trade deficit, in addition to those experienced in previous years, means the country is spending more US dollars than it is earning – with billions leaving the country each year.

The resulting shortage of US dollars has made it difficult for the payment of goods and services – including imports of food staples like maize.

“We are simply spending very much more than we have the ability to earn,” says John Robertson, a Zimbabwean economist and managing director at Robertson Economics.

“As a country we have lost much of our productive capacity, so most of the ways we used to make money are no longer there. When we were making money [through local production] we did not have to import that much… because we had goods on the shelves of the shops that were made by local companies.”

The central bank’s “unpopular” solution

In 2014 the central bank released ‘bond coins’ of 1c, 5c, 10c and 25c, pegged to the US dollar, and Robertson says this was a welcomed addition.

“Until then the lowest denomination was $1. But lots of things are supposed to cost less than a dollar – even a loaf of bread is supposed to cost 80c or 90c. So you need change and the bond coin made change possible.”

He adds that the amount allocated for bond coins was also considerably less than the proposed $200m for bond notes.

“I think it was about $50m used to mint the coins and $50m did not make a big difference to the money supply. It didn’t distort the value of the money out there.”

While $200m might not seem enough to distort the value of money in the economy either, Robertson is concerned the central bank will continue to print more.

“In our money supply we have about $5bn – so $200m is not a big percentage of that. But if the $200m was [printed] again five times it would be $1bn and that is a significant portion of the money in the country,” he highlights.

“There is a widespread belief that, once having launched some of these bond notes, the government will then launch many more of them. And for that reason I believe that as soon as it hits the streets its value will go down – maybe on the very first day by 1/10th of where it started… So I think it’s going to collapse.”

The central bank is applying other measures to curb the shortage of US dollars in the market. It has placed a $1,000 limit on the amount that can be withdrawn from ATMs and taken out of the country for travel purposes. It has also implemented a policy that 40% of US dollar foreign exchange receipts from the export of goods and services must be converted to rands and 10% into euros.

Bond notes could further reduce dollar supply

Thomas Sithole, an actuarial analyst and head of enterprise risk management solutions at Bluecroft Actuarial Solutions, notes the main difference between the bond coins and bond notes is that the coins were introduced to compliment the usage of US dollars in the economy, while the notes look to replace them.

He argues that a better solution for addressing cash shortages would be for the government to instead invest in digital money systems, like mobile money.

“Because by introducing the bond notes they haven’t yet addressed the real problem that is driving the illiquidity… They could reduce the amount of US dollars already in our country and they will reach a situation whereby they will have so many bond notes and very few US dollars. This is when the crisis or tipping point will come into play and things like a black market can emerge because the government will not be able to maintain that one-to-one relationship between the US dollar and bond note.”

Robertson believes that with no trust in the bond note, employees will not want to receive them as wages and shops will not want to accept them as payment, especially since they can’t be used to import products. The consequence could be that Zimbabweans start collecting and stashing US dollars as a safety net, which will only further reduce supply in the market.

“So the US dollars that are in circulation today are likely to disappear as people start to see these as more valuable and believe if they part with them they might never get them back,” he continues.

“But I believe there will be a ground swell of resistance and resentment against this and I think the government might decide to change it before its supposed to be brought into play. So the hope is that government decides its not going to do this anymore.”

Here are some of the outraged, supportive and plain humourous Twitter comments concerning Zimbabwe’s bond notes.

https://twitter.com/Keengstn/status/729598181370155008

The introduction of the #BondNotes gave me flashbacks of 2008! pic.twitter.com/GkfSUnkT4q

— Sue Nyathi (@SueNyathi) May 7, 2016

I hear #bondnotes are at design stage Im sure whoever is designing them wants to be paid in usd

— Gaza (@MrMtetwa_) May 9, 2016

A Zim Dollar is still a Zim Dollar even by any other name #BondNotes https://t.co/G49vvtNh7V

— Idriss A. Nassah (@mynassah) May 10, 2016

https://twitter.com/MgciniNyoni/status/729270785450364928

https://twitter.com/KalabashMedia/status/728161926186991616

2008 Season 2.#BondNotes

— Bwana Irvine (@irvinemance) May 5, 2016

https://twitter.com/deltandou/status/727989294279868416

Just picturing a situation where I am at an ATM trying to withdraw my hard earned USDs when suddenly #BondNotes… https://t.co/f6CUZeCbAA

— Kudzai Isaac Sadomba (@ogksad) May 4, 2016

this idea of #BondNotes could work, i mean look how the #bondcoins turned out

— Reneiloé | Mrimirwa (@reneiloe_m) May 9, 2016

The #RBZ statement on #bondnotes will certainly unnerve markets, foreign investors & will chill public confidence by a lot of degrees.

— campion mereki (@campionmereki) May 4, 2016

We like our economy shaken not stirred… #bondnotes #Zimbabwe

— Karin Alexander (@karin_kjalexan) May 4, 2016