Start-up snapshot: Ugandan street vendors step into the future

Start-up: Musana Carts, Uganda

Nataliey Bitature is founder and head of operations at Musana Carts, a social enterprise that has developed solar-powered vending carts targeted at street food traders in Uganda. A graduate student in the US, Bitature co-founded the business with her classmates Manon Lavaud and Keisuke Kubota. Bitature tells How we made it in Africa about the opportunity to solve street vendors’ energy and mobility challenges, and some of the risks her business faces. Below are edited excerpts.

1. What was the motivation behind your business?

In Kampala, many food vendors use charcoal and kerosene stoves, and ordinary tables made by local carpenters. You will find them stationed next to a store where they keep their charcoal, flour and extra eggs in the evenings – so they have to maintain a good relationship with the store owner. They also operate from the same location all day long, even when not making sales. And for some reason in our culture, all vendors stand next to each other and sell exactly the same thing. So this a competitive business with a lot of inefficiencies.

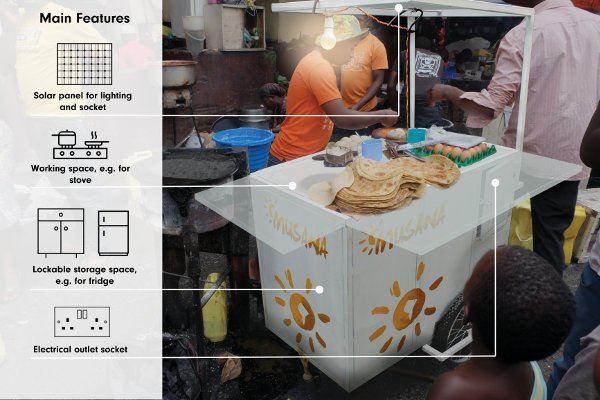

We realised when you introduce better energy infrastructure it affects the economic opportunities these vendors have access to. So we decided to design a solar-powered vending cart to sell to them, enabling them to both earn more and reduce their exposure to harmful emissions. The vendors we’ve spoken to told us they wanted something that looks good, has adequate storage space and, importantly, is mobile so they can go to where customers are, rather than stand in the same location all day.

We have partnered with a microfinance company to enable vendors to acquire the carts for about US$500. Our buyers will also access business and financial literacy training to best prepare them for this upgraded infrastructure. At the moment most street vendors in Kampala are not legal and have a very tenuous relationship with the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA). Hence, we are also working with the KCAA to get them licensed so they won’t be harassed or arrested.

We have already received orders which we expect to start fulfilling on a big scale in a few months. It is hard to find exact data, but there are certainly thousands of food vendors – from those selling fruit to hot foods – around Kampala. We are not worried about the numbers, this is a big market.

2. How did you finance your start-up?

We crowd-funded. Initially, we raised $10,000 from our friends and family. And this last month we raised about $25,000 through an Indiegogo campaign.

3. If you were given $1m to invest in your company now, where would it go?

We are actually hoping for that in September. We are finalists in the Hult Prize (a student social entrepreneurship competition) where we will be competing for a $1m prize at the Clinton Global Initiative annual meeting in New York.

We would put that financing into a professional workshop. Right now we are trying to manufacture the cart by outsourcing to different builders and suppliers. Ideally, to build this to scale and to bring the costs down, we need to get all the materials upfront. So we need a big working capital fund. We will probably need to import our solar panels rather than buy from local dealers in Kampala. We would also invest in well-trained staff to do the production, sales and training of our buyers.

4. What risks does your business face?

It is always difficult starting a business in a developing economy. We always have volatile situations and the rule of law is not respected as in developed economies. So things can change at a moment’s notice. If the KCCA decides to change their position this week, then we have a problem. We try to plan as much as we can to mitigate any time loss or money loss just because of the nature of the market.

Then there is also the risk of the cart not being as functional as we would expect. We are working with technology at the bottom of the pyramid, so it has to be different from mainstream products. Different solar companies involved in selling to rural areas – where there is limited infrastructure and technical capabilities – have broken the barriers, so we hope it won’t be too challenging. But whenever you bring a new product into a market, or a new type of technology, you are on a steep learning curve. You have to be ready to take feedback and criticism – as well as to iterate, change and adjust until it’s just what it needs to be.

5. Tell us about your biggest mistake and what you’ve learnt from it.

When we were in the field in Uganda researching, we felt sure we’d got everything from the vendors and understood the realities. But when we returned to San Francisco, we realised that we did not quite read the field accurately. We saw what we wanted to see. We should have tried to put ourselves in the shoes of the vendor, but I am afraid we did not. We made a lot of assumptions that were later difficult to make sense of. We have now learnt to listen better. Instead of getting them to confirm what you hope to be true, we have changed the way we ask questions, the way we do research and the way we analyse the things we observe.

I now truly see the importance of customers in your business. It is not so much about what you want to do, or what business idea you have. It is about what the customer needs and the solutions you are bringing to a problem. The most important people involved in our business are the street vendors.