Africa’s digital revolution needs data centres

By Kabir Chal (Actis Director: Real Estate, Nairobi) and Funke Okubadejo (Actis Director: Real Estate, Lagos). Actis is a growth-markets investment firm.

Have you ever wondered what happens every minute on the internet? The answer is a lot. The world’s most popular apps and websites have seen significant growth over the last four years and will continue to grow rapidly as more people access the internet and the cost of access falls. Internet users grew from 3.4 billion to 4.6 billion from 2016 to 2020 but the main story is rising use per capita. We live in a world where huge amounts of data are being produced and consumed. All of it needs a home and that home is the data centre.

The global data boom is not only being driven by consumer usage. Automation and machine learning are significant players in this story giving birth to what is widely known as the internet of things (IoT).

IoT refers to the interconnection via the internet of computing devices embedded in everyday objects, enabling them to send and receive data. The lead role however is cast to the cloud – the ethereal space out there where people store their memories, where companies host their applications and increasingly computing is taking place. To many of its end users, the cloud is a virtual concept, out of sight out of mind.

The reality is that cloud needs somewhere to live, somewhere that maintains the ambient conditions to allow it to operate at peak performance. That somewhere is the data centre. Cloud is responsible for the recent explosion in data centre growth globally.

Sub-Saharan Africa: High growth in data consumption, off a low base

Africa is one of the fastest-growing data usage regions in the world – albeit from a low base. In addition to the active mobile network operators, this has caught the attention of several global majors including Google, Facebook and Amazon, all of whom are making substantial investments to help boost Africa’s network infrastructure to cater for this demand. One of the key areas needing investment is the data centre sector which sits at the heart of the digital revolution.

According to the Ericsson Mobility Report, in 2019, 54% of sub-Saharan Africa’s mobile subscriptions were data users of which 11% were on 4G networks. By 2025, 72% of sub-Saharan Africa’s mobile subscriptions are expected to be data users with those on 4G networks growing to 29%.

From 2019 to 2025, sub-Saharan Africa is forecast to be the world’s fastest-growing region in terms of new mobile subscriptions – 4% per annum (compared to 1% in Latin America and China), with absolute subscription numbers second only to Asia.

Over the same period, smartphone subscriptions are forecast to grow at 9% per annum, second only to MENA. Sub-Saharan Africa is by far the fastest-growing region globally in terms of monthly mobile data consumed (per smartphone) – 52% per annum. Whatever scepticism there is to be had around affordability of, and access to, data in Africa, the reality is that data usage is growing at tremendous rates and infrastructure investment has not kept up.

Latency and regulation point towards hosting data locally in Africa

To date, a large amount of content is being stored in offshore data centres (mainly Europe and the US) servicing African markets through sub-sea cable linkages. This was fine at a time when usage levels were lower but started to prove problematic as an increase in users began to challenge bandwidth and the broader network investment, thereby introducing greater latency. This has caused several international cloud and content providers to explore hosting their content locally in data centres and, in the last three years, heralding the entries of Facebook, Google, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, etc. to South Africa, Kenya and Nigeria.

The renewed global focus on data sovereignty has prompted several African countries to revisit their own regulations which has brought further impetus to data centre development across the continent. For instance, in Nigeria, the government requires data to be hosted locally for key sectors – oil & gas, financial services and public sector.

Latency and data sovereignty regulation are two major drivers for hosting data locally. Cloud made its first major appearance in Africa last year with Azure establishing a presence in two South African data centres and AWS building three of its own facilities in Cape Town. Reading across from trends in other markets, one would expect Google to follow suit very soon. These majors are also actively looking at East and West Africa and the expectation is that they will have an initial preference to host their cloud platforms in third-party data centres.

Lowering costs for local hosting requires investment in network infrastructure

It is easy to understand why Google and Facebook may be well placed to have good insights into Africa’s data consumption and indeed the trajectory of its growth – as the adage goes, actions speak louder than words.

In 2019, Google announced the Equaino cable that will connect the West Coast of Africa with Europe – the project being only the third privately funded cable project by Google.

In 2020, Facebook announced that it was joining to lead Project Mercury, an ambling subsea cable project. The 2Africa cable will connect Africa’s circumference starting and ending in Europe. Both cables will add a huge amount of internet capacity to Africa and help to substantially reduce broadband costs. Localising the hosting of content and increasing the peering, the exchange of data directly between internet service providers (ISP), rather than via the internet) carries substantial benefits to the end user: cost and latency being the most obvious. In 2010, the Internet Society set an ambitious goal to see 80% of African internet traffic hosted locally by 2020.

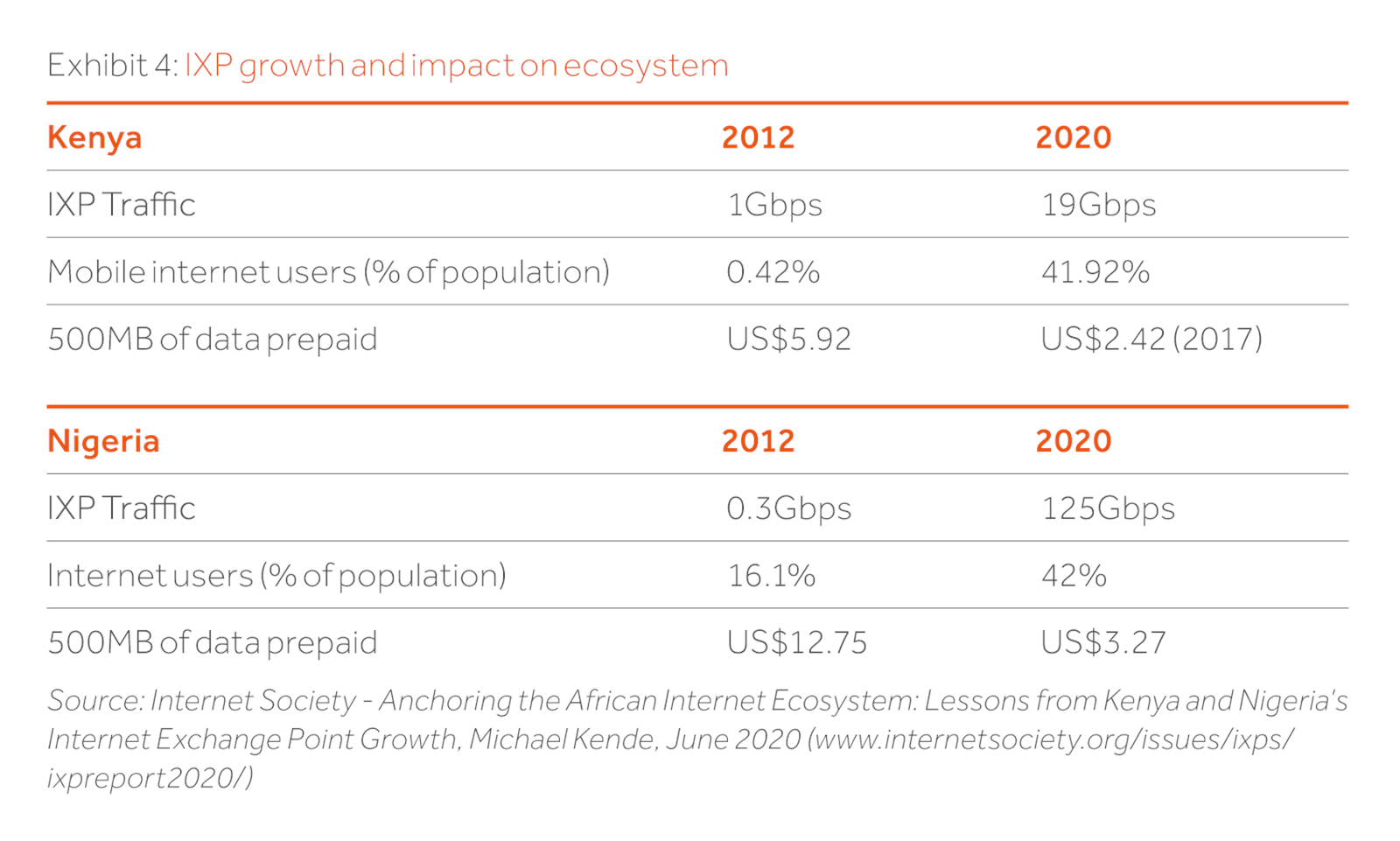

In order to achieve this, pieces of the ecosystem needed to come together: Africa needed more subsea cable capacity, fibre networks needed to be expanded, more data centres needed to be built and internet exchange points (IXPs), where ISPs and content delivery networks (like Facebook) exchange internet traffic, to be established. A case study done in 2020 on Kenya and Nigeria has shown tremendous progress.

In 2012, approximately 30% of each country’s traffic was localised; today that figure has grown to around 70%. Growth in peering volumes through IXPs in both markets was exponential as were cost savings from exchanging traffic locally (in doing so avoiding expensive international transit).

The IXPs in Kenya and Nigeria have seen their respective peering traffic volumes grow 19-fold and 400-fold respectively with significant cost savings estimated at $6 million per annum and $40 million per annum respectively. In addition to lower data bundle prices for consumers, both countries have seen significant increases in the number of mobile internet users – 100-fold for Kenya and four-fold for Nigeria to 42% of the population.

IXPs are hosted in data centres and it will be no surprise to note that over the same period data centre capacity in Nigeria has grown three-fold, whilst Kenya’s has almost doubled. That said, Xalam Analytics contextualise in their latest publication, Africa Data Centre Gold Rush, that the entire installed data centre capacity in sub-Saharan Africa is less than half than that of London’s and is broadly on par with Paris.

Covid-19 and its restrictions have accelerated the digital revolution

Covid-19 and the lockdown restrictions that followed had a huge impact on data consumption globally. Data traffic increased by between 20-100%, on a like-for-like basis, across the world’s largest markets. The pandemic ushered in a closer relationship with the internet where people now rely on it more for work, education, communication and entertainment. It is unlikely that this will materially abate once the pandemic eases, putting further urgency on the build-out of network infrastructure, like data centres, to cope with the increase in traffic and dependency. Across major developed market economies, Ericsson reported a 10-20% increase in mobile data traffic in Q1 2020. Over the same period, MTN Nigeria recorded a 60% growth in data revenues, supported in part by the addition of 1.7 million active data users to its network. Both the IXPs in Kenya and Nigeria recorded record daily spikes in peering volumes during Covid-19’s lockdown restrictions.

An early mover opportunity exists to establish a network of pan-African data centres

Notwithstanding the strong sector fundamentals and secular growth trends supporting the data centre sector in Africa, it remains relatively underinvested in sub-Saharan Africa (excl. South Africa). There are a number of reasons for this, including: it is a capital-intensive sector; there is little local expertise in developing and operating data centres; most markets present challenges when dealing with power, real estate and fibre connectivity.

The impression of a challenging operating environment in Africa may deter international strategic players from entering sub-Saharan Africa (excl. South Africa) on a greenfield basis, providing an opportunity for investors who have experience of investing in the development of power, infrastructure and real estate assets across Africa.

Actis, through its Africa Real Estate Fund, established a $250 million pan-African data centre platform. The platform is focussed on establishing a network of data centres in Africa’s largest markets following a buy-and-build strategy. Actis has partnered with an experienced ICT private equity firm, Convergence Partners as well two industry experts Tim Parsonson and Frank Hassett. The platform completed its first acquisition of a majority stake in Nigeria’s leading data centre, Rack Centre.

This article was first published by Actis.